May 19, 2025, U.S.A.

(The following article is based on a talk I gave at the “AI in Quantitative Finance Seminar” by the University of Chicago, held in Hong Kong on April 24 and 25, 2025)

(For other articles published by Dr. Chou, please visit Dr. Chou’s Blog page)

Introduction: For all the industries that are considered as early adopters of artificial intelligence (AI), finance is one of the earliest. Within finance, quantitative investment and trading is the subfield that started exploring both the hardware systems (such as GPUs for derivative pricing) and software tools (such as neural networks for price forecasting) even before they became mainstream sensations. The reason for such early adoption of AI in quantitative finance is two-fold: first, quantitative finance researchers and practitioners accumulate data that are often well-structured (such as high-frequency limit order book data), thus relatively straightforward to apply newly developed AI models to solving real-world problems; secondly, quantitative investors and traders are on the constant lookout for innovative ways to conduct return forecasting and risk management practices, thus always being incentivized to try out new quantitative models in their investment strategies. However, many quantitative investors and traders are also rather pragmatic users of AI and can be critical of AI-based models and infrastructure if investment made in AI research and infrastructure build-out cannot be relatively quickly justified.

With the advancements of generative AI since the official rollout of OpenAI’s ChatGPT product in late 2022, many quantitative investors and traders are excited about the potential of these new tools that can help them achieve better results, such as more accurate price forecasting models and more powerful research and trading infrastructures. This latest generative AI development is in fact the second wave of AI in recent years with its impact on quantitative investment and trading practices, with the first wave being the adoption of research and trading infrastructure that has been based on machine learning and deep learning packages and are often implemented in AI-friendly programming languages such as Python. Although the development is still in its early stage, it is worth some thinking about how this second wave of AI – exemplified by Large Language Models (LLMs) and AI Agents – is shaping up and potentially further impact the practices of quantitative investments and trading.

Large Language Models and Financial Forecasting: LLMs are a new generation of natural language processing (NLP) models that are based on sequential models within the deep learning arena, where many AI technologies have been developed to process and understand human languages. Although it is often kept as industry secrets, the number of parameters of an industry-strength NLP model (such as those command-recognizing tools used in smartphones, car navigation systems, etc.) is often estimated up to a few hundred million to a few billion. As a comparison, it is estimated that ChatGPT, the generative AI LLM by OpenAI, may have up to 1.7 trillion parameters, and Llama-2, an open sourced LLM platform by Meta, may have up to 70 billion parameters. One of the key technological developments that are crucial to the success of an LLM such as ChatGPT, is the Transformer model, originally developed by Google and has been greatly expanded and improved to handle more complicated natural language processing problems than the original seminal Google paper described. A key consequence of these developments in the Transformer technology is the gradual built-up of “learning” or “reasoning” capability of LLMs. The best example of this “reasoning” capability is the DeepSeek R1 models, in which a user can observe how such a model reasons and develops its answers to a question (or a sequence of questions) posted by a user.

A basic assumption in quantitative investment and trading can be described as “history repeats itself”: within the information set that a quantitative investor/trader can fully explore, if a “pattern” appears within this information set with high statistical confidence to the investor/trader (such as a statistically significant relationship between two variables, and at least one of them is investable), the investor/trader will often assume that such pattern will reappear in future data and can be exploited to build forecasting models used in real-world investment and trading activities. Many financial data are of the type of time series, indicating the sequential nature of the data with temporal causalities. Such causal effects also appear in human reasoning processes with human languages. Therefore, it is natural to contemplate if an LLM can help identify such “patterns” like many statistical inference tools that quantitative analysts have been using.

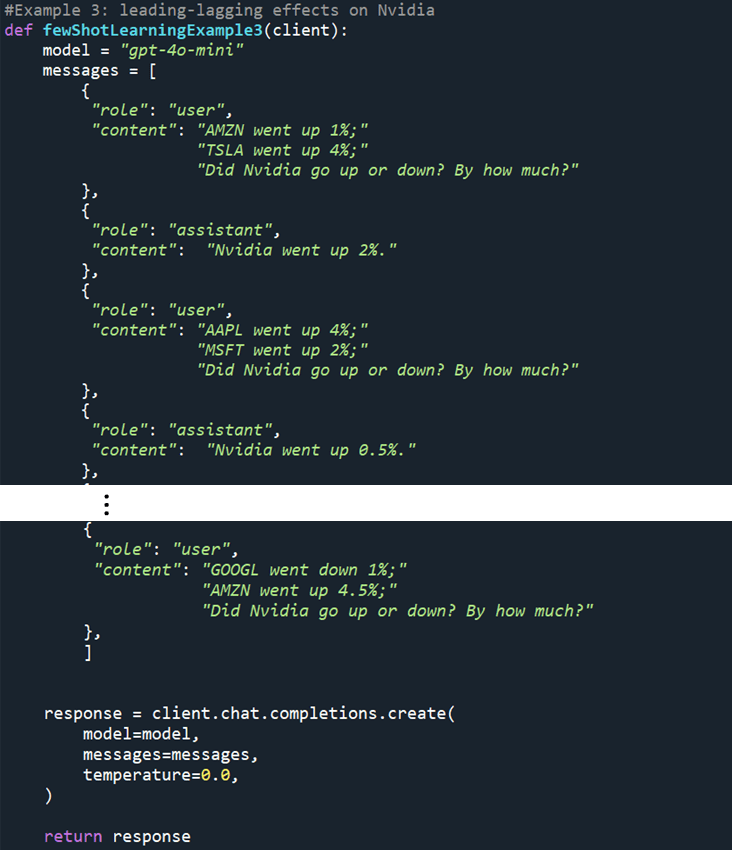

Like many other statistical tools, LLMs can indeed help quantitative analysts seek out such “patterns” from historical data. However, because LLMs are best at processing natural languages with contexts, the simplest way to build forecasting models for real-world use is to train an LLM with historical data, arranged in human language sequences. Figure 1 is an example of the so-called “few shot learning” approach to training an LLM to learn from historical data then give a forecasting answer with a new prompt. This example shows that, when framed as a sequence of questions and answers in human language, a historical time series data can be used by an LLM to detect patterns and use the pattern to produce forecasting results.

Figure 1: An example of training an LLM using the “few shot learning” approach to predict stock returns using human language prompts.

Although it can be argued whether the above example is an efficient way of using a highly structured data to predict future price, it is intriguing to find out if an LLM – when fed in the same time series data that help train statistical models – can also produce forecasting results of similar or better qualities compared to other statistical models. Given that an LLM is often considered as a model with rather different structures from a statistical model (such as linear regression), quantitative analysts can be quite interested in such a novel approach, especially when the LLM approach is somewhat “orthogonal” to traditional statistical approaches.

LLMs and Factor-based Investing: Factor-based investing has been a common approach to portfolio investing for many decades. This methodology is rooted in the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). EMH claims that asset prices reflect the information content possessed by market participants, and the participants’ pricing of an asset cannot go beyond their information content; as a result, if the market possesses the same amount of information content as each individual participant does (that is, the market is fully transparent in terms of information about the asset), no participant can outsmart the market. In the real world, a market participant can only approximate the information content that a market possesses; mathematically, this means that a market participant can model the price of an asset based on its “exposures” to various “factors” that the market exhibits, and this is shown in equation (1) below.

Here E(Ri) is the expected return of the ith asset, and E(Fk) is the expected value of the kth factor. betai,k is often called the exposure of the ith asset to the kth factor, and ai can be considered as the regression interception for the ith asset, while ei is the noise term for the regression for the ith asset. Note that factors are often identified by quantitative analysts who study the market. Common factors that quantitative investors and traders use are often from the groups of fundamental factors, technical factors, liquidity factors, risk factors, sentiment factors, etc. Once the values of such factors are determined, equation (1) can be used to make forecasts on asset returns by building a linear regression model between an asset’s next period return data and the asset’s current and/or historical factor values.

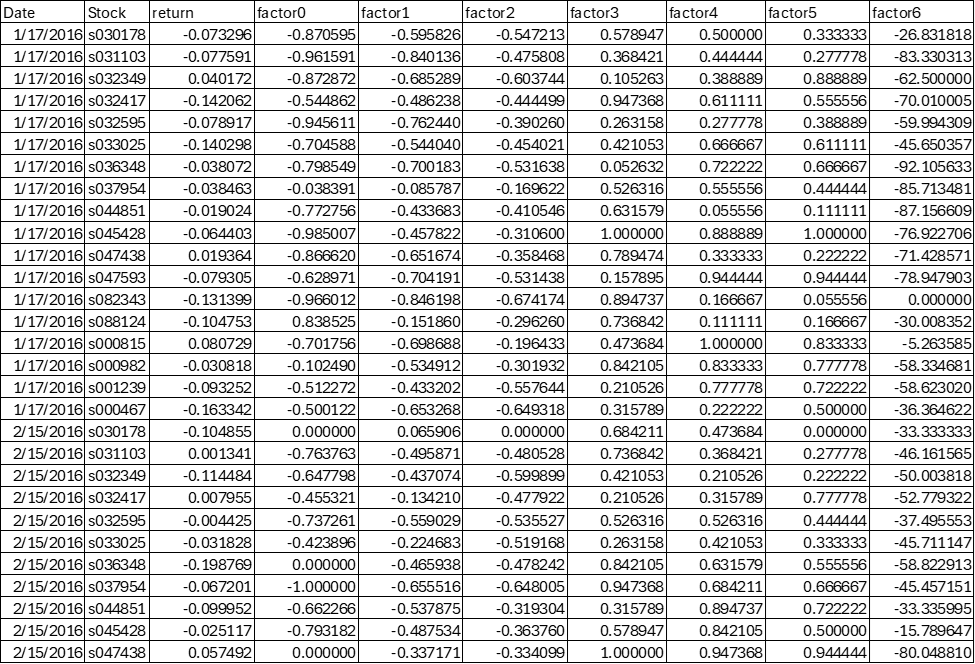

As machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) tools are more widely adopted, quantitative analysts often build ML or DL models in addition to a linear regression model in forecasting. Figure 2 provides sample factor value data and stocks’ future return data, both are time series data. The factor values are often used as “features” and the future returns are often used as “labels”. It is a common practice nowadays that the features are fed into ML/DL models that are optimized to obtain the minimum value of a pre-defined metrics that measures the distance between forecast returns and labels. The exact process often involves many technical details such as training, validation, testing, feature selection and engineering, ablation testing, etc.

Figure 2: Sample factor value data.

With the emergence of LLMs, it is natural to consider how LLMs – like existing ML and DL platforms – can help conduct return forecasting tasks. Given that LLMs are trained to understand human languages and the contexts of conversations between a user and an LLM, it makes sense to convert a structured data shown in Figure 2 to a sequence of “questions and answers” and use the so-called “few shot learning” approach to train an LLM to make return predictions. In many ways, this “factor-to-Q&A” conversion is like the example shown in Figure 1, with the only difference in that the factor model case involves the simultaneous forecasting for all stocks included in the portfolio. With gpt-4o, an LLM from OpenAI, we are able to test such forecasting approach using an LLM and compare its forecasting results with other models. It shows that, with a relatively simple set-up of the LLM back-testing arrangement, the prompted LLM generates an information coefficient of 0.0141 for monthly return forecasting for stocks. As a comparison, a linear regression using the same factor data and back-testing set-up gives an information coefficient of 0.0135. We believe that the LLM approach has potential to be further trained to obtain better results as it has not been fully fine-tuned in terms of forecasting parameters due to a constraint on token numbers on the gpt-4o model that we use. Still, we are encouraged by the preliminary results of applying factor model data to LLMs for return forecasting.

It is also worth mentioning that there have been publications that discuss how LLMs can be used to conduct asset price return forecasting, such as sentiment-based trading signals that are based on LLM-analyzed news data, etc. For traditional factor-based investment strategies, sentiment is often considered as one kind of factor that can be used with other factors in building forecasting models. The above approach with preliminary results shows that LLMs can be utilized in conjunction with factors other than sentiments.

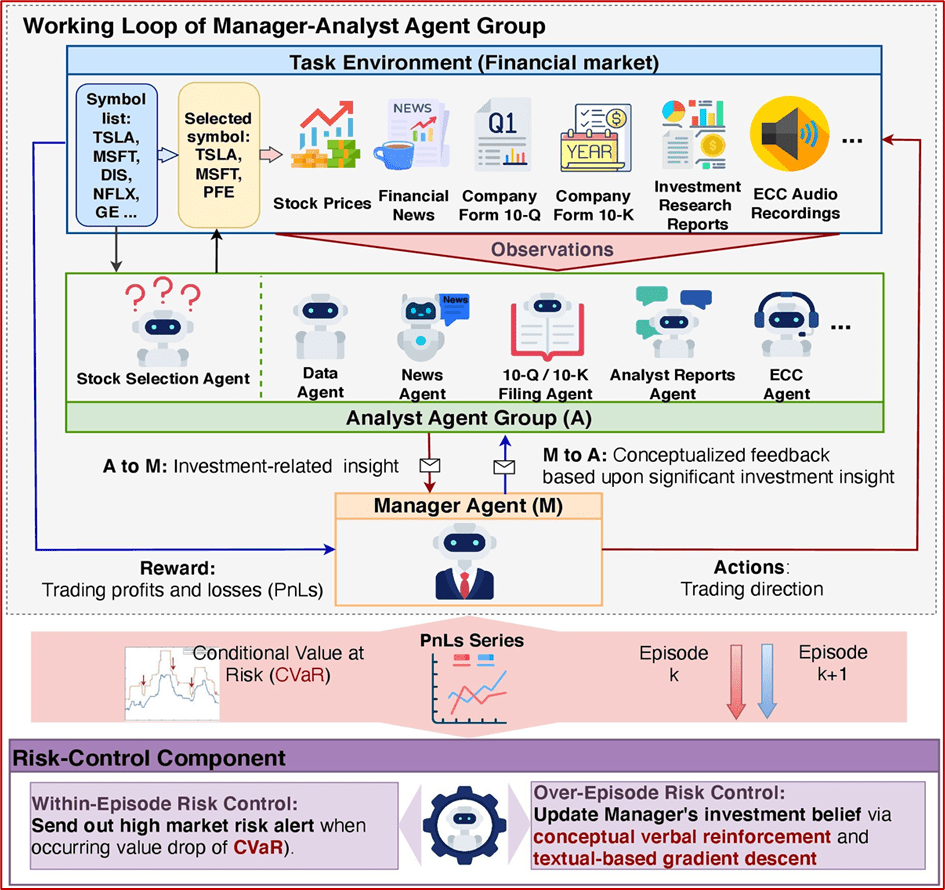

The Impact of LLMs and AI Agents on Quantitative Investment and Trading: Although the use of LLMs is still relatively new to many quantitative investors and traders, there have been discussions on how they can help improve quantitative investment and trading practices. In addition to the above example of using LLMs and factor data to forecast returns, LLM-enabled AI Agents are believed to help streamline the operations of a financial institution. An AI agent can be considered as a self-sustained AI system that reflects on its environment, conducts specific tasks based on pre-defined goals, interacts with other AI agents when necessary, and adapts to new environment and updated goals. In many cases, an AI agent needs to have one or more LLMs as its backbone intelligence platform to fulfill the tasks assigned by a human or another AI agent. With such AI agents, a quantitative investor or trader can build an AI system that mimics the current operations of an investment firm or a trading desk. For example, the “Manager-Analyst” Agent Group design discussed in Yu et al (2024; see also Figure 3) is an interesting pattern that an investment firm can use to build such an operation platform in which many quantitative analysts can perform various tasks such as data gathering and cleaning, stock and sector analysis, investment-related tasks such as return forecasting and portfolio construction, etc. What is interesting – and assuring to potential users of such platforms – is that a “Manager” AI agent can be trained to conduct managerial tasks such as planning, task assignments to individual “Analyst” AI agents, managing work progresses of individual “Analyst” AI agents, forming final investment decisions, and so on.

Figure 3: The AI Agent system with the “Manager-Analyst” design pattern (see Yu et al; arXiv:2407.06567v3 [cs.CL] 7 Nov 2024).

We believe such LLM-enabled AI Agent systems can greatly enhance the productivity of quantitative investment firms and/or trading desks, especially small- and medium-sized investment firms. As discussed by Kelly et al (2024), as long as the measurement errors of factors are contained, the more features are included in a return prediction model, the more benefit one can obtain from a ML/DL-based model in forecasting. Constrained by limited financial resources, small- and medium-sized investment firms lack the research capabilities of studying a large number of investment factors. As a result, these firms tend to focus on a limited number of factors that are important to their investment strategies. On the contrary, large firms can often afford to study and incorporate more factors in their investment strategies, thus leading to potentially better investment performance. With LLMs, a small- and medium-sized firm can construct LLM-enabled AI Agent systems on which many automated “Analyst” AI agents can help collect data, conduct factor analysis and back-testing, and recommend top performing new factors to be included in investment strategies. Of course, this also means that even small- and medium-sized investment firms still need to invest in LLMs and AI Agent systems, which often come with steep learning curves and potentially high maintenance costs.

The “Holy Grail” of AI-enabled Quantitative Investment and Trading: It is worth noting that LLM-driven quantitative investment strategies may potentially suffer from “forward looking bias” because the LLMs used in these analyses are just “snapshots” of these models released on certain dates and of particular versions. In other words, the LLMs did not exist on historical dates that are considered in back-testing analysis and, as a result, back-testing results that predate the release date of the LLMs may be potentially exposed to forward-looking bias because the LLMs used in back-testing are likely trained with “newer” data than many dates included in the back-testing.

For many quantitative investment firms and trading desks, the only way to address such a “forward-looking bias” issue is via “scenario analysis”: for dates after the release date of an LLM used in the analysis, one can create “market scenarios” that are of different economic consequences. In other words, instead of assuming that “history repeats itself” for future investment decision making, a quantitative analyst can create “close to reality” ensembles of market conditions, such as bull and bear markets, high inflation and low inflation environments, the appearances of natural disasters, etc. In this way, a quantitative analyst can try to exhaust as many outcomes as possible via simulations in which his/her investment strategies can be tested.

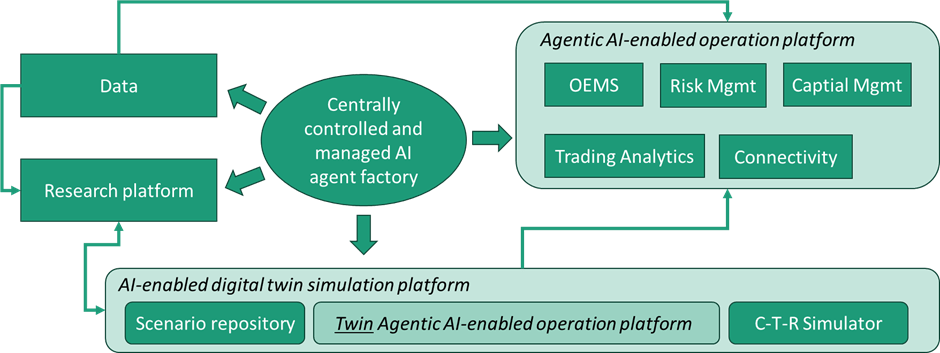

We call such ensemble-based “close to reality” simulation-enabled environment as the “holy grail” of AI-enabled quantitative investment and trading platform design and development. In achieving such as “holy grail”, we believe the concept of “digital twin” can be considered. For example, Figure 4 provides a high-level illustration of such a “holy grail” design of quantitative investment and trading platform. At the center of such a design is a centrally controlled and managed AI agent factory, in which AI agents that are capable of different tasks can be manufactured, maintained, re-trained and re-tasked to ensure up-to-task performance status.

Figure 4: The “holy grail” design of AI-enabled quantitative investment and trading platform.

Conclusions: Like Python changed infrastructure for quantitative investments and trading, LLMs/AI Agents will change the infrastructure for quantitative investments and trading. However, what can be different between the impact of ML/DL/Python and the potential impact of LLMs/AI Agents is that the latter may help streamline the operations of a quantitative investment firms or trading desk, thus further “democratizing” many aspects of quantitative investment business (such as low-cost alpha research via LLM-enabled AI agents). Nonetheless, we believe that all quant funds may still want to invest in human-based domain-specific research and testing capabilities, although AI will be more and more useful tools in this process. Throughout this whole process, small- and medium-sized firms will likely benefit more in the short term from LLM/AI Agent paradigm, especially from research productivity point of view; however, this also means a relatively steep learning curve until material benefits can be achieved. Keep learning and keep being trained!

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this document are solely those of the author and may not necessarily that of ECC Info; no part of this material can be regarded as investment advice or suggestions from the author and/or ECC Info; all computer codes are provided for illustration purpose only.

References:

Yu Yangyang, Zhiyuan Yao, Haohang Li, Zhiyang Deng, Yupeng Cao, Zhi Chen, Jordan W. Suchow, Rong Liu, Zhenyu Cui, Zhaozhuo Xu, Denghui Zhang, Koduvayur Subbalakshmi, Guojun Xiong, Yueru He, Jimin Huang, Dong Li, and Qianqian Xie, FinCon: A Synthesized LLM Multi-Agent System with Conceptual Verbal Reinforcement for Enhanced Financial Decision Making, arXiv:2407.06567v3 [cs.CL] 7 Nov 2024

Kelly, Brian, Semyon Malamud and Kangying Zhou, The Virtue of Complexity in Return Prediction, Journal of Finance, Vol. LXXIX, No.1, Feb 2024